You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the LORD your God am a jealous God.

Exodus 20:4–5 ESV

Definition

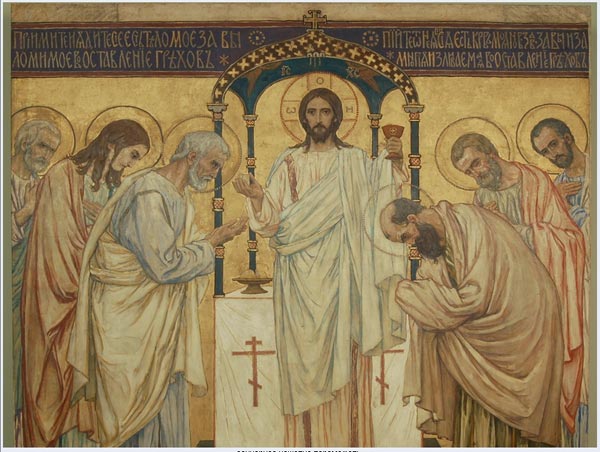

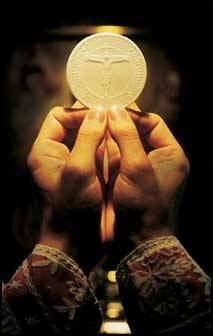

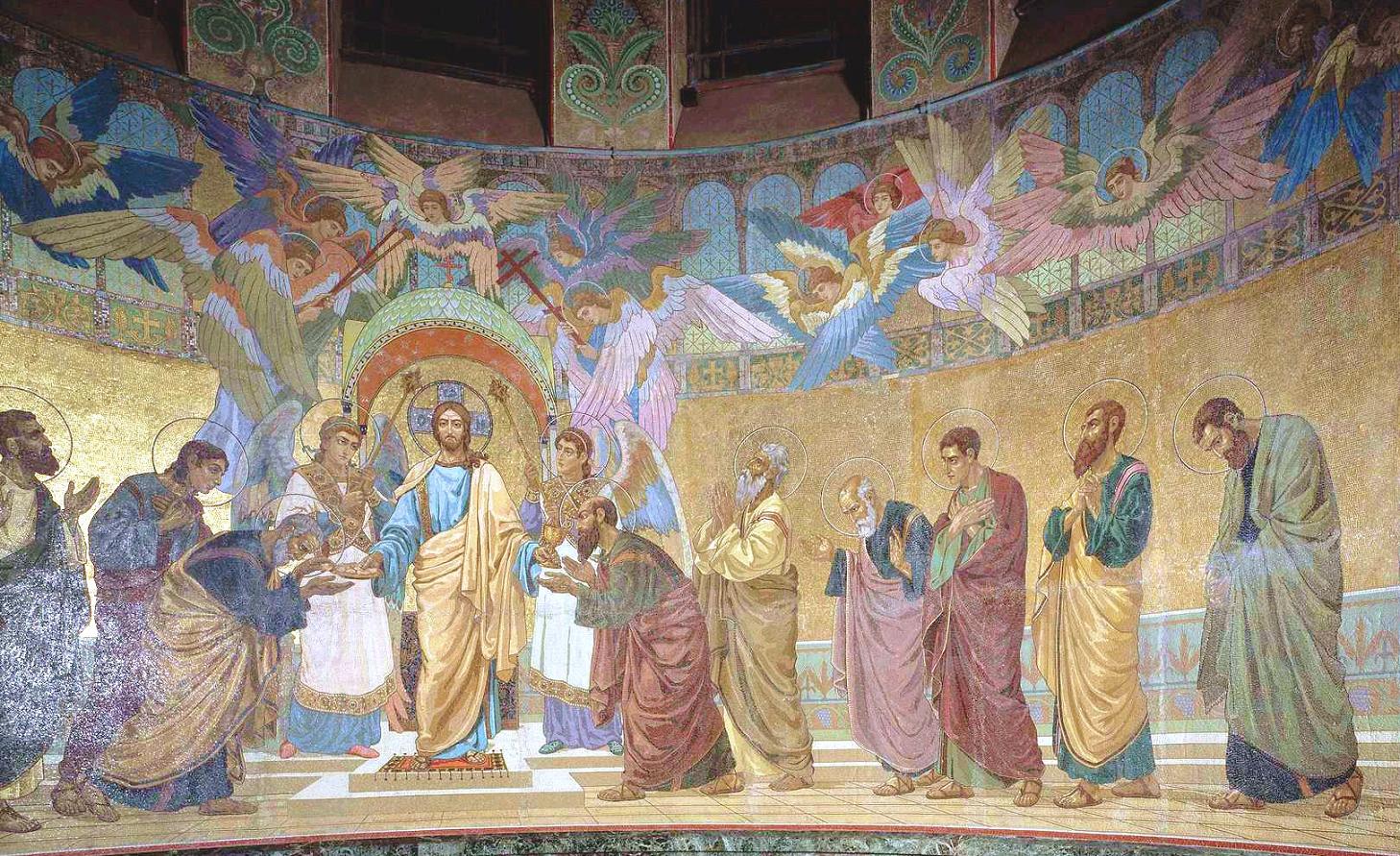

Eucharistic adoration is a sign of devotion to and worship of Jesus Christ, who is believed to be present in the consecrated host. The consecrated host is the physical presence of Christ in the sanctified bread and wine which Roman Catholics, and Anglo-Catholics, believe to be the actual body and blood of Jesus Christ.

Transubstantiation

The consecrated host is placed in a monstrance and stationed on the altar for viewing at regular times during the week. The devotional and worship practice of adoring and praying to the consecrated host is practiced in local parishes, shrines, and monasteries. The belief that Christ is physically the wafer as displayed in the monstrance and is present in the midst of the congregation is a theological extension of the doctrine of transubstantiation. With some exceptions, those Roman Catholic, and Anglo-Catholic, churches who endorse Eucharistic adoration accept as true the doctrine of transubstantiation.

The doctrine of transubstantiation is the belief of the Roman Catholic Church that the outward (accidents) appearance of the bread stays the same after consecration, but the host’s inner nature (substance) is changed into the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ. These categories of accidents and substance are the thought of Aristotle not the theological workings of the ancient fathers of the Church or the biblical teaching of Jesus Christ and Paul the Apostle.

Medieval Development

Eucharistic adoration is not an ancient practice; it began in Avignon, France on September 11, 1226. Public adoration of the Blessed Sacrament began as a thanksgiving celebration for the victory of France and the Roman Catholic Church over the Albigensians in the later battles of the Albigensian Crusade. King Louis VII desired that the sacrament be placed on display at the Chapel of the Holy Cross. The multitude of adorers brought the local diocesan bishop, Pierre de Corbie, to suggest that the display continue indefinitely. With the permission of Pope Honorius III, the idea was approved and adoration continued mostly uninterrupted until the French Revolution.

Genuine Catholicity?

Eucharistic adoration is not encouraged in the Orthodox churches of the East neither has this form of worship been practiced everywhere for all the time by all churches. For a practice or doctrine to be considered orthodox: it must have been received by the undivided Church (East and West), stood the test of time, and agreed upon by the consensus of the early fathers. This triple test of ecumenicity, antiquity, and consent is called the Vincentian canon and it is the overarching test for genuine Catholicity. In my view, the practice of Eucharistic devotion, that is displaying a monstrance containing a consecrated host for worship and prayer, does not pass the test of the Vincentian canon. Therefore, Eucharistic devotion does not meet the criterion as an acceptable practice within the Great Tradition and is not to be considered a theological conviction of the ancient faith.

Russian Orthodox theologian, Alexander Schmemann, states that Eastern Orthodoxy does not practice the elevation of the bread and wine for special adoration.

The Purpose of the Eucharist lies not in the change of the bread and wine, but in the partaking of Christ, who has become our food, our life, the manifestation of the Church as the body of Christ. This is why the gifts themselves never became in the Orthodox East an object of special reverence, contemplation, and adoration, and likewise an object of special theological “problematics”: how, when, in what manner their change is accomplished.

[Alexander Schmemann, The Eucharist: Sacrament of the Kingdom (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 1998), 226.]

Eastern Orthodoxy’s Eucharistic focus is not on the change in the elements, but on the presence of Christ, the power of the Holy Spirit, and the mystery of faith encountered in the ancient liturgy. Eastern Christians do not adore the consecrated bread outside the sacred liturgy.

The Reformation

As would be expected, the Evangelical Reformers of the sixteenth century had grave doubts about the practice of Eucharistic adoration. They decried its use, discouraged participation, and condemned its practice within Roman Catholic Church. John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli and their colleagues in Geneva and Zurich, respectively, issued a statement as to their common agreement concerning the nature of the Lord’s Supper. The document, Heads of Agreement on the Lord’s Supper, was written after the failure of the Marburg Colloquy.

The Marburg Colloquy was an attempt to achieve a concord between Martin Luther and Zwingli over the nature of the Eucharist. Luther believed in real presence of Christ and Zwingli declared the elements of bread and wine to be merely symbolic. Luther and Zwingli’s disagreement was volatile and very public. Their discord was rending the Protestant movement at its very heart.

John Calvin felt that Protestantism needed at the very least to declare its unity on some matters regarding the Lord’s Supper. Article Twenty-Six states Geneva and Zurich’s condemnation of Eucharistic adoration:

If it is not lawful to affix Christ in our imagination to the bread and the wine, much less is it lawful to worship him in the bread. For although the bread is held forth to us as a symbol and pledge of the communion which we have with Christ, yet as it is a sign and not the thing itself, and has not the thing either included in it or fixed to it, those who turn their minds towards it, with the view of worshipping Christ, make an idol of it.

The English Reformers agreed with Calvin and Zwingli writing in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Faith, “The sacraments were not instituted by Christ to be gazed at or carried about, but to be used properly†(Article XXV, updated language). With a few exceptions, Evangelicals continue to reject the use of a monstrance, they feel that confining God to an object is a form of idolatry.

Idolatry

Many Roman Catholic, and Anglo-Catholics, are sincere in their desire to dwell in Christ’s presence, but it takes very little effort on the part of the Enemy to turn a sincere devotional activity into idolatry. Roman Catholics describe the consecrated host as “the physical body of Jesus,” thus the presence of the host in the monstrance is said to increase the anointing of the Holy Spirit in the sanctuary. It is said, if the monstrance is removed, God’s presence is removed. If “the host and precious blood” are returned to the sanctuary, Christ’s presence has returned.

To state that God’s presence is contained or limited within a physical object is a form of idolatry (Exodus 20:4-6). Idolatry reduces God the Creator to a material object of creation thereby limiting his attributes of omniscience, omnipotence, and omnipresence. The Lord is no longer Spirit, but an object which can be controlled by human beings (Isa. 40:18-23). It grieves me as a believer, pastor, and theologian, that God’s precious gift to us of Holy Communion has been twisted and made into an object. I have no doubt that that the adorers are sincere in their desire to be in the presence of Christ. However, it will not take long for the flesh, or the Enemy, to bring misunderstanding about the nature of salvation causing much personal sorrow and emotional pain to all involved. Arguments that Eucharistic adoration is a blessing to parishioners by increasing the presence of God in the church building is experiential and subjective without basis in scripture or tradition.

The Ancient Liturgy

Instead of the Table of the Lord being a place of participation in Christ, it becomes a night stand for observing God from a distance. Adoration confuses the physical object with its Author, and the location of God with a material entity, and limits God’s attributes to a place and time. Alexander Schmemann’s main criticism of Eucharistic adoration is that the practice isolates the Eucharist from its purpose: communion with God (pg. 227). The Eucharist is removed from its context in the liturgy as the communion of the Church with Christ and places Christ at a distance, objectifying the Eucharist in a manner not consistent with the whole meaning of the Lord’s Supper.

Holy Eucharist is intended to be place of an encounter with the living resurrected Christ. In Scripture, seven theological images or truths of the Eucharist are revealed: remembrance, communion, forgiveness, covenant, nourishment, anticipation, and thanksgiving. These truths cannot be experienced if we are watching instead of participating.

Summary

Eucharistic adoration as a belief and practice is erroneous: it does not reflect the teaching of the Bible or life of worship found in the Ancient Church. The practice is not promoted in the Orthodox East and is not consistent with full and complete participation in the Holy Eucharist.

Caveat: The views expressed in this blog post are entirely my own and are not necessarily the views of the Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast, Southeast Archdiocese, or the International Communion of the Charismatic Episcopal Church (C.E.C.).